History shows that since 1947, when domestic failures, political crises or unrest in Kashmir intensify, New Delhi’s political discourse has often leaned on a familiar device: blame Pakistan and mobilise nationalist sentiment. The recent flood of commentary around “Operation Sindoor” fits this 75-year pattern. Mr Mohammad Kunhi’s piece, provocatively titled “India’s Missing Friends During Op Sindoor”, deserves a response not because it is clever, but because the logic it advances — a tidy friend-versus-foe narrative built atop selective facts — is precisely the kind of argument that escalates tensions while closing down diplomacy.

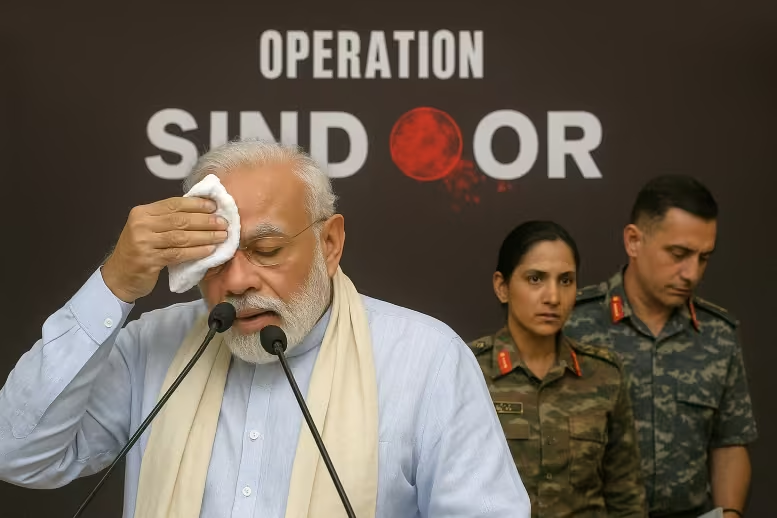

Some critics have labelled the operation’s public justifications as fanciful; others point to actual reports of a coordinated Indian military action called “Operation Sindoor” in May 2025. International outlets covered the operation and nations urged restraint, making clear that the event itself is a matter of public record rather than invention.

Whether or not the operation occurred, the issue at stake is how it is framed: presenting it as a test of friendship or as a moral litmus test for other states turns policy into theatre. Framing becomes propaganda when selective facts are marshalled to foreclose debate and to normalise escalation.

Naming war is political theatre — ‘Sindoor’ weaponises culture to make reconciliation politically unthinkable.

Language matters. Naming an operation “Sindoor” — a term loaded with cultural and religious meaning — cannot be treated as accidental. The deliberate invocation of charged symbols risks fusing military action with civil-religious identity in ways that polarise domestic audiences and alarm neighbours. Such symbolic choices make reconciliation harder: when the language of statecraft borrows religious imagery, opponents are not only political rivals but are morally othered.

Kunhi’s list of “reliable friends” — France, Russia, Israel — rests largely on public declarations and arms-industry ties. But international relations are not friendship bracelets; they are transactional and strategic. Independent data show that India remains one of the world’s largest importers of major arms — a structural reality that complicates claims that arms sales equal political loyalty. Characterising arms exporters as “friends” risks conflating commerce with alliance and obscures the incentives that drive policy.

The foreign policy expectation Kunhi advances — that Western powers should unconditionally back India — misunderstands how contemporary diplomacy functions. Calls from major powers for “restraint” and “dialogue” are not betrayals of friendship but standard practice to prevent escalation between nuclear-armed states. India’s own policymakers regularly invoke “strategic autonomy” to justify independent decisions; the international community exercises the same discretion when it seeks to stabilise a region. S. Jaishankar’s recent remarks underline that India publicly defends such autonomy as a principle.

Kunhi’s dismissal of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and China as merely “friends of the enemy” flattens decades of diplomacy and commerce into an infantilised binary. Pakistan’s ties with Turkey and Azerbaijan are shaped by shared historical and multilateral bonds; its relationship with China is underpinned by large infrastructure and economic projects such as the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that are substantive and long-term. Reducing these relationships to an accusation of automatic hostility toward India betrays a shallow conception of global politics.

The region’s future depends on replacing nationalist spectacle with steady diplomacy, legal frameworks and genuine conflict resolution.

When opinion pieces convert military episodes into proof of domestic legitimacy, two things follow. First, they normalise a politics of spectacle that rewards immediate, militaristic responses over patient diplomacy. Second, they feed an arms market logic: if military posturing is the metric of strength, demand for hardware follows — and suppliers see friends in customers, not allies. This is not to trivialise India’s security concerns; rather, it is to point out that the pathway from rhetoric to rearmament is well-trodden and often self-fulfilling.

If the point is national security, then the correct response is not to hawk moral certainties but to pursue durable, non-violent outcomes. That means reopening diplomacy, engaging neutral frameworks such as the UN Charter and international mediation mechanisms, and insulating crisis responses from celebratory domestic spectacle. It also means interrogating the domestic incentives that make jingoism politically profitable — and legislating against the normalisation of military theatre as policy.

Mohammad Kunhi’s column is a symptom of an older disease: the temptation to substitute spectacle for substance. Whether Operation Sindoor is reported as an actual operation or presented as a rhetorical device, the danger remains the same — the reduction of complex geopolitics into a morality play that rewards escalation and sells armaments. The region’s future cannot be secured by such fictions. The more promising route is the harder one: rebuilding spaces for diplomacy, respecting legal frameworks, and refusing to let nationalist theatre substitute for the steady work of conflict resolution.